Paul Leo

The Advocate for the JewsFather: Friedrich Leo

Mother: Cécile Leo

Siblings: Erika und Ulrich Leo

After first studying history in Göttingen, Paul switches to theology in Tübingen and Marburg, where the New Testament scholars Rudolf Bultmann and Adolf Schlatter number among his teachers. His father dies the year World War I breaks out and the Leos have little money to survive on. The Marburg Academic Association, which Paul Leo re-establishes, has the educator Adolf Reichwein as one of its members; he will later be executed by the Nazis in Plötzensee Prison in 1944. Leo writes his dissertation on the ancient Church Father and monastic bishop Basil of Caesarea. Due to his ill health, he is forced to take frequent leaves of absence from his studies. He attends conventions and writes articles for the young ecumenical movement, particularly for people who have grown estranged from the Church. In Norderney, his first parish posting, contacts with Jewish neighbors are routine. In 1931, his wife Anna dies, shortly after giving birth to their daughter of the same name.

After the Nazis come to power, Paul Leo, who is classified as a “three-quarter Jew,” makes it his personal mission to assist so-called “Judeo-Christians.” With the aid of August Marahrens, a nationalist bishop of the Lutheran Regional Church of Hannover who has curried favor with the regime through proclamations of loyalty, Leo is able to formulate incisive arguments for his cause, which he proceeds to promulgate on the lecture circuit throughout Germany until 1938. Paul Leo, too, has a conservative and patriotic bent, but makes it a point of emphasizing that hatred for Jews and Christian faith are polar opposites. In Kirche und Judentum (“The Church and Judaism”), a memorandum commissioned by Bishop Marahrens and first presented in June of 1933, he argues as follows: “For the church, the Jewish Question can only consist of her asking whether the Jews are baptized or unbaptized. The unbaptized ones are the objects of her missionary love, while the baptized are fully fledged members of her congregation.” In his appraisal, Leo accepts neither of the two paths pursued in Germany up until that time – the assimilation championed by Moses Mendelssohn and the expulsion or destruction of the Jews – as viable for the future. He expects his institution to take a clear position: “The church must earnestly demand from the government that it respect two key things in the state’s political fight against the Jews: the honor and the person of the Jews...” The church must, so he argues, become the advocate of these sufferers vis-à-vis the state. He holds that Jewishness is to be defined not in ethnic terms, but rather on the basis of the Jewish religious ethos. The solution of the “Jewish question” is something that must be left to God alone. "Assuming that the complete solution of the Jewish question under the principle of assimilation is total absorption into the German Volk, then the complete solution under the principle of racial purity would be the annihilation of all Jews.”

Leo belongs to a circle of pastors in Osnabrück that has developed in the territory of the Regional Church of Hannover as a spin-off of the dissident “Confessing Church” and that recognizes what the state’s claim to totalitarian rule is: an attack on the vocation of Christians. As early as in April of 1933, these clergymen proclaim from their pulpits that the “Kingdom of God” is “the revelation of the eternal world to people of all nations and races through Christ.”

Ende September 1933 hatte Pastor Leo bereits seine staatliche Teilzeitstellung als Gefängnisseelsorger verloren, 1935 kündigt der Osnabrücker Oberbürgermeister ihn als Seelsorger am Städtischen Krankenhaus. Der Gemeinde Haste, in der Leo daraufhin unter wachsender Zustimmung der Gemeinde als Prediger eingesetzt worden war, wird im Frühjahr 1938 vom Staat der Entzug finanzieller Förderung und der Genehmigung für einen Kapellenbau angedroht. Leo verzichtet daraufhin auf sein Amt, um die Gemeinde nicht unter Druck zu setzen. Kollegen plädieren vergeblich für ihn, die Kirchenleitung versetzt ihn gegen seinen Willen in den einstweiligen Ruhestand. In den folgenden Monaten bereitet er Kandidaten der „Bekennenden Kirche“ in einem Untergrundseminar auf ihr Pfarramt vor. Am 10. November, während der Verhaftungswelle der Pogromnacht, wird er ins KZ Buchenwald verschleppt und dort misshandelt. Im Lager kann er Andachten für Christen jüdischer Herkunft abhalten. Für seine Freilassung, die nach sieben Wochen erfolgt, setzen sich der Heidelberger Stadtpfarrer Hermann Maas, ein Pionier des christlich-jüdischen Dialogs, und der Bischof von Chichester George Bell, ein ökumenischer Mitstreiter, ein.

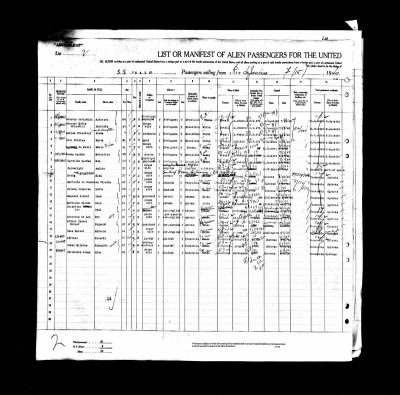

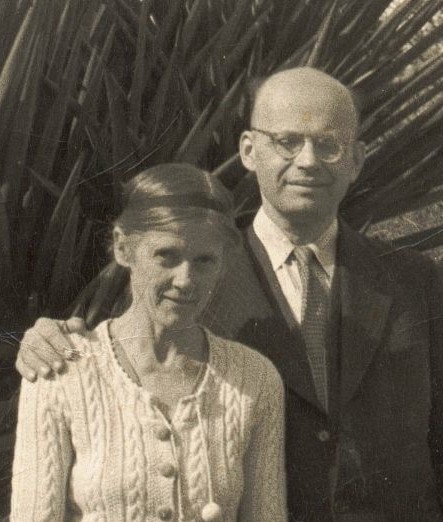

In April of 1939, the SS newspaper Das Schwarze Korps (The Black Corps) publishes an article entitled “Yid Leo Pockets Church Tax” in which it attacks the church for paying Paul Leo a pension: "The state imprisons a criminal Jew, while the church bestows the selfsame Jew with gifts from funds that it collects with the aid of the state.” By this time, however, Paul Leo has already followed his eight-year-old daughter to safety in Holland, having sent her ahead in a special train full of children. Here, he tends to Christian emigrés of Jewish origin in a refugee camp. Following his emigration, the Regional Church ceases to make any further payments. Together with his daughter Anna, his brother Ulrich Leo and his partner, the metal sculptor Eva Dittrich, whom he knows since 1937, he travels to America by way of England. Eva Dittrich is at first denied a US visa and has to wait in Venezuela. Leo spends the first year teaching church history at a Presbyterian seminary in Pittsburgh. In 1940, after marrying his second wife in a Presbyterian chapel in Caracas, he takes up postings at Lutheran parishes in Texas. His children Christopher and Monica are born in 1941 and 1944, respectively. The family decides against a return to the Hannover Regional Church after 1945. In 1951, Paul Leo becomes professor for New Testament studies at the Wartburg Theological Seminary in Dubuque, Iowa. This is where he dies on February 10th, 1958, during a lecture in which he explains the Greek term evangelion (gospel), or “good news.”