Moses Mendelssohn

The Jew of BerlinFather: Mendel Heymann

Mother: Rachel Sara Wahl

Siblings: Saul, Jente

At the age of fourteen, the budding scholar resolves to follow his revered teacher Fränkel from Dessau to Berlin. This requires passing muster with the local Jewish community leaders – no small feat, given their instructions from the Prussian authorities to discourage impecunious Jews from settling in the city where the royal family resided. Though bereft of means, the young autodidact develops into the intermediary of an intellectual network surrounding him. He learns old and new Western languages, while mastering High German and the European scholarly canon, which provoked conflict with the rabbis who favor cultural separatism. He improves his residency status by obtaining a position as a tutor for the textile manufacturer Isaak Bernhard. After becoming a bookkeeper for Bernhard’s firm, he quickly works his way up to managing director and finally to full partner. Though not his real calling, this bread-and-butter job allows Moses Mendelssohn, the civil name the self-made scholar opts for in this time, to finally secure his residency in Berlin and his family’s livelihood.

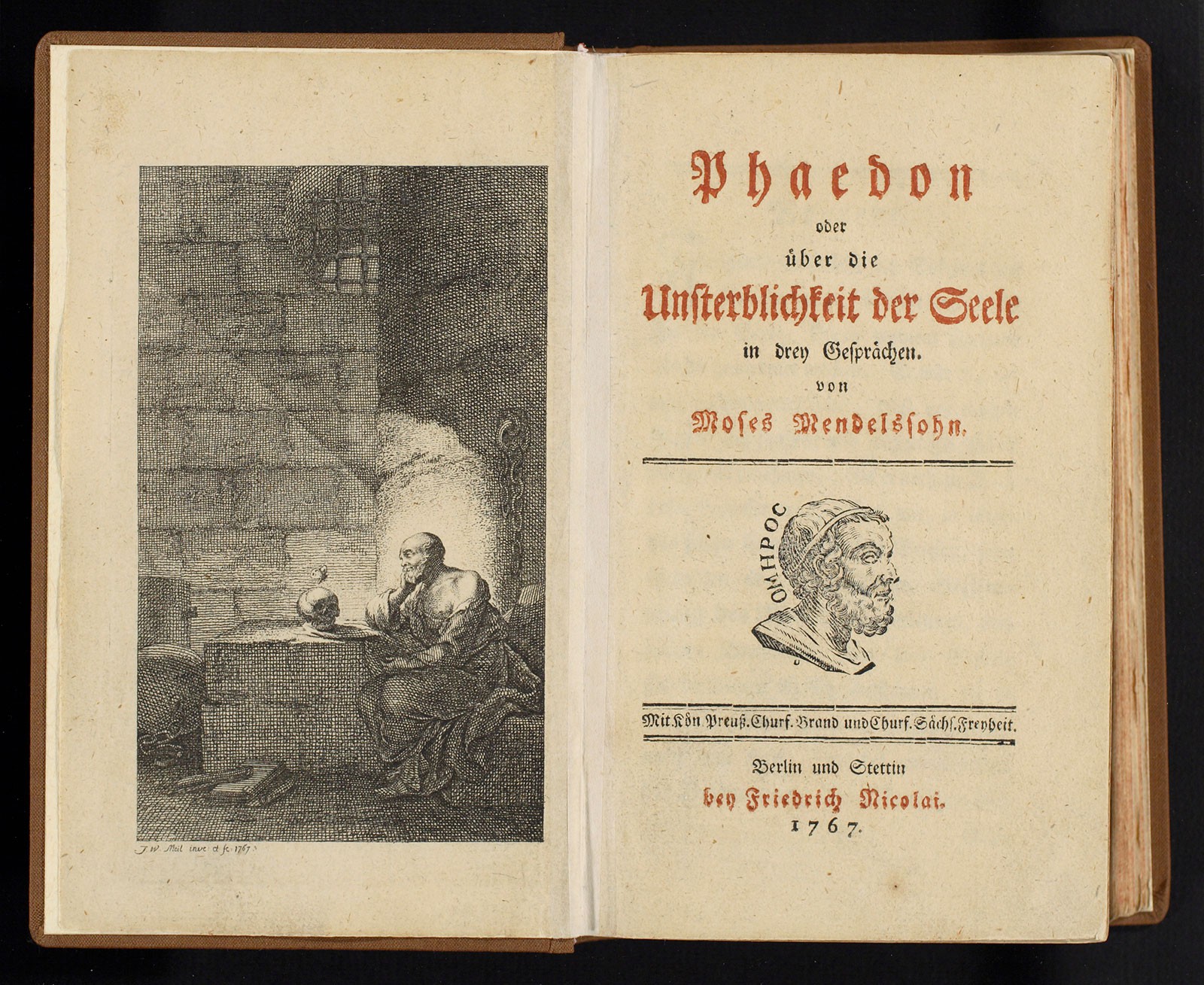

His acquaintance with the publisher Friedrich Nicolai and the writer Gotthold Ephraim Lessing developed into a trio of friends whose debates, critical reviews, essays, and published discussions become the stuff of cultural history. Moses’ marriage at 32 to Fromet, the daughter of a Hamburg merchant, eventually produces 10 children, six of whom survive. His townhouse on Spandauer Strasse develops into a forum for open discussion and debate, a model for the cultural salons that evolved later. Moses also becomes a best-selling author with the release of Phaedon: On the Immortality of the Soul, this being a topic of great interest to his contemporaries. Translated into several languages, the work makes the “Jew of Berlin” famous throughout Europe.

Moses Mendelssohn expounds on ideas introduced by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Christian Wolff in the fields of logic, mathematics, and religion and joins their efforts to explain the universes’ harmonious order. When the Prussian Royal Academy announces a competition for essays on Evidence in the Metaphysical Sciences (1763), Moses submits the winning entry. (Kant’s comes in second.) In his text, he synthesizes experience and reason while emphasizing the primary role of everyday practice. Moses the aesthete and precursor of the psychologists wishes to reconcile the moral mission of art as a vehicle for rational insights with a theory of art’s independence in what he terms a “game of illusion.” By his contacts, publications, public discourses, and correspondence, he champions the concept of tolerance and the universality of human rights. His charisma and radiant, upstanding personality stand him in good stead in this endeavor. His friend Gotthold Ephraim Lessing uses him as the model for “Nathan the Wise,” the main character of his eponymous play.

A transformational cultural figure, Moses’ translation of the Torah into German paves the way for his co-religionists to learn the language of the Christian majority society and to participate in its literature and art, to which he himself is passionately drawn. As both a pious Jew and “wise man of the world,” he helps to reconcile the revealed laws of Judaism with enlightened reason, while encouraging the Jewish community to break out of the intellectual ghetto. A modernizer, he counsels Jewish congregations that find themselves torn between tradition and assimilation. He also advises sympathetic Prussian officials on how to reduce discrimination. His renderings of Biblical texts into the German language are published using the Hebrew alphabet.

In his essay “Jerusalem: On Religious Power and Judaism,” he shows himself to be far ahead of his time with his ideas on the freedom of conscience and the separation of church and state. He is a pioneer of the Jewish Enlightenment or Haskala, whose key players include David Friedländer, founder of the Jewish Freyschule (Free School), Isaac Euchel, publisher of the first Hebrew magazine, Der Sammler (The Collector), the poet Hartwig Wessely, and the teacher Herz Homberg. The reform projects of the Haskala, which seek to build bridges between religions, not only facilitate the Jewish minority’s integration but also nurture the development of a modern German-Jewish culture, whose lessons still serve as guideposts for the social ideals of our pluralistic present.

Given the discrimination that Jews of his generation are subject to, Moses’ dealings with the authorities are a double-edged sword. King Friedrich II has the scholar summoned to Potsdam, for example, but never receives him. Though the King is willing to grant him recognition and a residency permit as a silk dealer, he blocks the philosopher’s induction into the Prussian Academy of Sciences and refuses to grant his family a more secure residency status. On instruction of the Jewish community, Mendelssohn writes verses in praise of the royal court, but is also bold enough to lampoon the monarch’s own poetry in a critical review. He inspires his friend Christian Konrad Wilhelm Dohm, a member of Prussia’s military Council, to write On the Civil Improvement of the Jews (1781), a book which proves influential in France and other Western European countries. Another luminary influenced by Moses is Count Honoré Mirabeau, who visits Berlin shortly after the philosopher’s death and publishes an essay on his legacy. As a member of the National Assembly during the French Revolution, Mirabeau raises and implements many of the ideas he absorbed in Berlin in the Assembly’s debate on human rights.

When the Protestant theologian Johann Caspar Lavater calls on Moses to have himself baptized as a Christian, Mendelssohn rebuffed him. The heated public debate that this provocation ignited leaves Moses with a nervous disorder that plagues him for the next seven years. Towards the end of his life, another seven years on, he becomes embroiled in further controversy when he publicly defends his late friend Gotthold Ephraim Lessing against charges of pantheism and atheism. Weakened by the strain, Moses Mendelssohn dies at the age of 56. Berlin's entire Jewish community is joined in paying their final respects by numerous Christians and members of the aristocracy. All shops are closed that day.