Eleonora von Mendelssohn

The Tragic DivaFather: Robert von Mendelssohn

Mother: Giulietta von Mendelssohn

Siblings: Francesco popup:yes, Angelica

The glamorous shots taken later, during her glory years on the stage in the Roaring Twenties and early 1930s, present her as an unapproachable diva. “She was beautiful enough to make your eyes pop out,” her colleague Elisabeth Bergner was to reminisce. “As educated as a whole university; and as intelligent as six devils, and as angelic as only an angel can be. She was also the most unhappy human being I ever met.”

A baptismal bowl used by the families of Robert and Franz von Mendelssohn, now exhibited at the Jewish Museum in Berlin, also bears Eleonora’s engraved name. The observation she is recorded as having made during the Nazi period – that anyone with her name must perforce be Jewish – has less to do with religious conviction than a need to express solidarity. A solidarity which she also extends to her baptismal godmother Eleonora Duse, the great theater star of the day. Venerated by both Eleonora and her brother Francesco, Duse is a long-time mistress of their father Robert von Mendelssohn until his death 1917. It is among Duse’s circle of fans that the Berlin banker is introduced to his 27-year-old bride, the Italian pianist Giulietta Giordigiani. Later, his widow is accused of engaging in financial skullduggery to exact revenge upon the aging theater diva, who is a client of the family bank. This intensifies tensions between the siblings and their mother Giulietta, who also happens to be a supporter of Mussolini. Eleonora’s life-long ability to empathize with others, sometimes at her own expense, also applies to her brother, who lives an openly gay lifestyle as a rich heir in 1920s Berlin. This sensitivity for others is also reflected in her personal vulnerability: After undergoing an abortion, the young woman becomes permanently addicted to morphine, initially just a painkiller.

Despite her drug habit, Eleonora’s stage career takes her to the Schauspielhaus in Düsseldorf as well as to the leading stages of Berlin and Munich. She attracts notice playing opposite Renate Müller, Veit Harlan, Berta Drews, Luise Ulrich, Blandine Ebinger, Rudolf Platte, Käthe Haack, Paul Graetz, Helene Weigel, Lotte Lenja, Werner Krauss, Paula Wessely, and Attila Hörbiger, working with directors like Jürgen Fehling, Otto Falckenberg, and Leopold Jessner. The critics praise her “soulful body language and deft vocal modulation” as well as her avoidance of cheap showmanship: She is, they say, a “born portrayer of interior life.” In her role as Bettina Clausen in Max Reinhardt’s premiere of Gerhart Hauptmann’s Vor Sonnenuntergang (“Before Sunset”), she even wins over the feared critic Alfred Kerr: “Eleonore Mendelssohn portrays another human being with complete self-denial – wonderful. In her wretched gait, stuttering speech, and inflamed gaze, we see an extremely courageous picture of truth. A paragon of truth.” On January 21st, 1933, she plays the mystical beauty Helen of Troy in Faust Part II opposite Gustaf Gründgens and Bernhard Minetti at the Prussian State Theater. It is to be her last role in Germany.

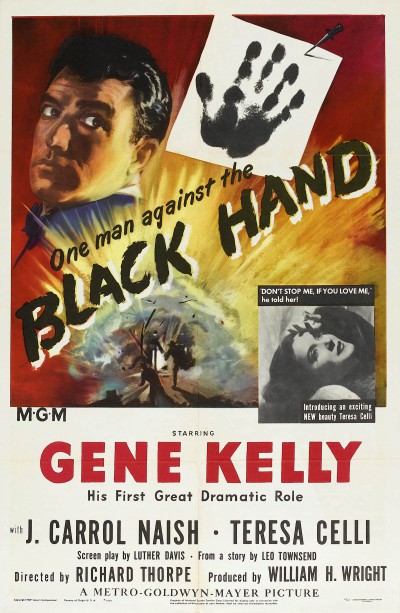

In order to finance a European tour by Max Reinhardt, she sells works of art from among the family heirlooms. After her beloved directs the Biblical spectacular “The Eternal Road” by Franz Werfel and Kurt Weill in New York, she becomes active as a fundraiser on his behalf. In 1935, she emigrates to the United States with her brother Francesco. Her attempts to re-start a major career on Broadway are unsuccessful and she only manages to appear in the odd New York theater production. During World War II, she moonlights as a news announcer for German-language broadcasts at the Office of War Information. The money she draws from a Mendelssohn family foundation is not sufficient to cover her lifestyle or to care for Francesco, whom she has to rescue from his recurring life crises. The only role she lands in Hollywood is in the film noir “Black Hand” (1950), where she plays an impoverished and desperate Italian lady whose husband has been murdered by the mafia.

Eleonora seems to be a tragic figure in her own biopic when it comes to her relationships with the distant, ultimately unattainable men in her life: the father who dies young, the volatile brother, the idol Max Reinhardt, and the conductor Arturo Toscanini, whom she later pursues with equal yearning. She is married four times: From 1919 to 1925, to the pianist Edwin Fischer; from 1927 to 1936, to Austrian cavalry captain Emmerich von Jeszenzky, who tries to wean her away from her drug habit; from 1938 to 1944, to her fellow emigré actor Rudolf Forster, who denies her wish for the healing gift of a child and returns to the “Third Reich” instead. In 1947, she ties the knot with the homosexual actor Martin Kosleck, who ekes out a living in Hollywood by playing Nazi characters. Francesco suffers a stroke and ends up in the hospital, joined soon thereafter by Martin Kosleck, who has tried to commit suicide over a love affair gone wrong. On January 24th, 1951, Eleonora von Mendelssohn, who has been looking after both men, takes her own life with a toxic cocktail of ether, pills, and injections.