Fromet Mendelssohn

The Lady Director from AltonaFather: Abraham Gugenheim

Mother: Glückche Mirjam

Siblings: Joseph, Brendel, Blümche, Nathan

Fromet loses her mother when she is just one year old and will live under the same roof as her stepmother for a long time. In 1761, Fromet is courted in Altona by the witty, incredibly cultivated but hunchbacked Berlin textile merchant Moses Mendelssohn, who shares her love of literature. During this time, the 24-year-old girl’s father, Abraham Gugenheim, is away on a business trip to Vienna, trying to stave off impending bankruptcy.

Though a highly disparate romantic couple, Fromet and Moses decide to get married without the traditional matchmaking formalities – an independent and modern approach that seems to predispose the saga of the Mendelssohn family. This version of events is later contradicted, however, by the writer Bertold Auerbach, who claims that it was the groom and Fromet’s father who took the initiative. In Auerbach’s version of the romance, Moses, already smitten, notices that his hump has uneased the young damsel and is about to take his leave: “At last, after he had cleverly steered the discussion in this direction, she asked, ‘Do you also believe that marriages are sealed in heaven?’ To which Mendelssohn replied, ‘Most assuredly, and what’s more, let me tell you something extraordinary that happened to me. When a child is born, you see, an announcement is made in heaven: this one or that one will be matched with her or her. And so when it came my turn to be born, my future wife was announced to me, whereby I was also told, that, alas, she would have a hump – a really terrible one. ‘Dear God,’ said I, ‘a girl who’s deformed can easily become bitter and hardened; a girl should be beautiful. Dear Lord, then give me the hump, but let the girl be svelte and pleasing!’” Whereupon Fromet, so the story goes, embraces him, overcome. This anecdote probably does contain a core of truth, at least when it comes to the charm which Fromet’s suitor exhibits in winning over the bride and the openness with which she allows herself to be swept off her feet.

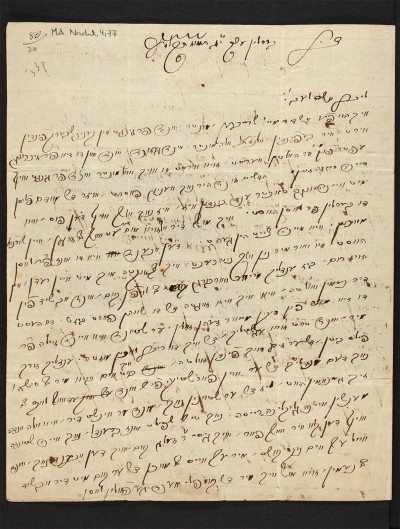

Sixty-seven letters from their courtship and engagement are preserved. They touch on many things: their declarations of affection “in the denuded garden house;” future projects for the beloved girl’s education; honesty, emotions, friendships, and relationships; literature and morality in high society; family quarrels and reciprocal gifts; the preparations for their wedding in Berlin on June 22nd, 1762. The spirited relationship between the couple and the bride’s vivacious tone shine through this correspondence, and continue to do so in the letters which Fromet writes later on during the marriage.

The successful synthesis of economic acumen and a love for the arts becomes a recurrent theme in the Mendelssohn dynasty. Although the patriarch Moses places free thinking above all human passions, it is the textile business that secures his income and his residency permit. Instead of marrying the rabbi’s daughter who was recommended to him, he chooses a merchant’s daughter. The first documented business deal outside Moses’ employment at the silk workshop is a loan granted in 1765, which the couple jointly sign off on: 4,000 reichstalers to their landlady, with the building at Spandauer Strasse 68 serving as collateral.

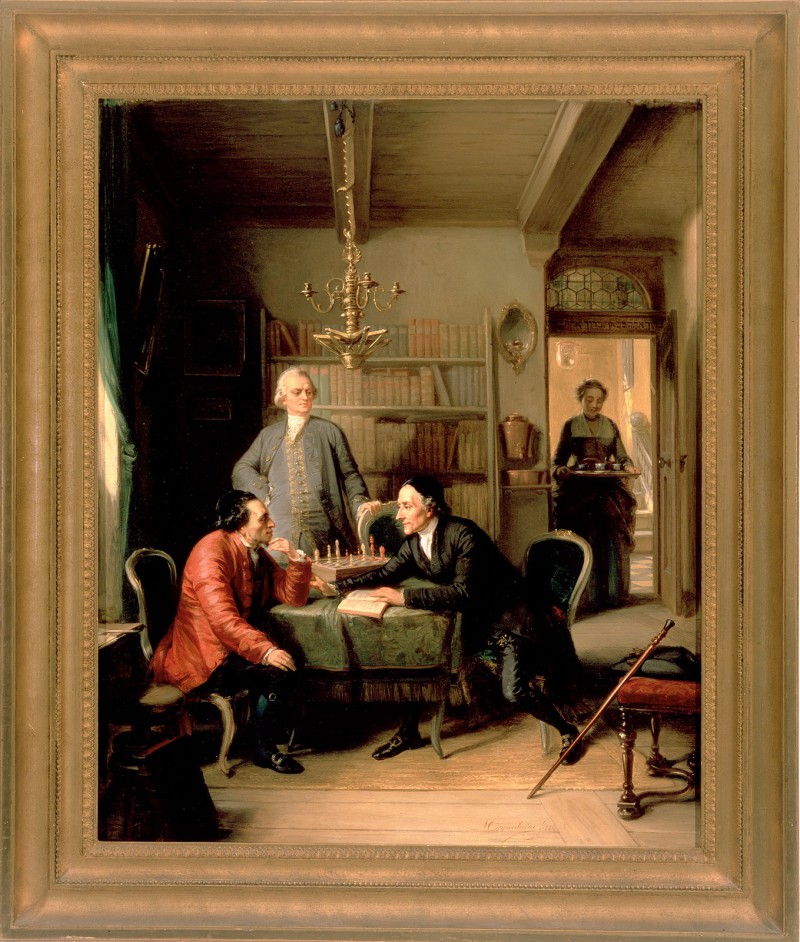

As a mother, lady of the household, and hostess, Fromet is the strong, intelligent woman behind the philosopher who, as an entrepreneur and scholar, is sought out by a wide range of business and discussion partners, students, and acquaintances, but is often overworked. She runs the household which the Mendelssohns share with other relatives and with the progressive live-in tutors of the children. She also controls the purse strings and is said to sometimes count out the almonds and currants she serves as snacks to the guests who come to practice their debating skills in this haven of free thought.

Fromet sees Moses, the inveterate charmer, through many crises. She takes an interest in favorite topics and makes friends with fellow thinkers of the Enlightenment such as the Reimarus siblings in Hamburg and the Lessings. She loses four children early but raises six to adulthood; she never recovers from the loss of her eldest daughter Brendel, who abandons her Jewish husband and the Jewish faith. Though she herself married for love, Fromet seems to have no objection to the pre-arranged nuptials of two of her daughters. After Moses’ death in 1786, the widowed Fromet finally obtains the right of residence for herself and her children which the king has so long withheld. She buys their house, but soon feels the memories crowding in on her. After selling the property, she and her stepmother Vogel join her favorite daughter Recha in the provincial town of Neustrelitz, where the family used to spend refreshing summer holidays at the home of the court factor Nathan Meyer. At the beginning of the new century, she moves back to her native Altona with Recha, now divorced, and Recha's former father-in-law Nathan Meyer, a close friend of the family.

She gives her wedding dress, which the couple had converted into a Torah curtain (parochet) and donated to the synagogue in 1775, to the local synagogue. As a fashionably styled widow, she exhibits an undiminished zest for life, enjoying card games, comedies at the theater, and strolls on the ice with her young granddaughter Fanny. She becomes the nucleus of her family, which has largely followed her back to Hamburg. When she dies, five days after the edict proclaiming the emancipation of the Jews of Prussia iss issued, her banker sons Joseph and Abraham have already fled the city with their families to escape the French occupiers. She does not live to see reconciliation with Brendel, the black sheep of the family. Her favorite daughter Recha Meyer, who is by her side at the end, announces in the obituary published in a Hamburg newspaper that her mother passed away “gently and without significant pain.”