Marie Baum

A Woman of the Modern AgeFather: Wilhelm Baum

Mother: Flora Baum

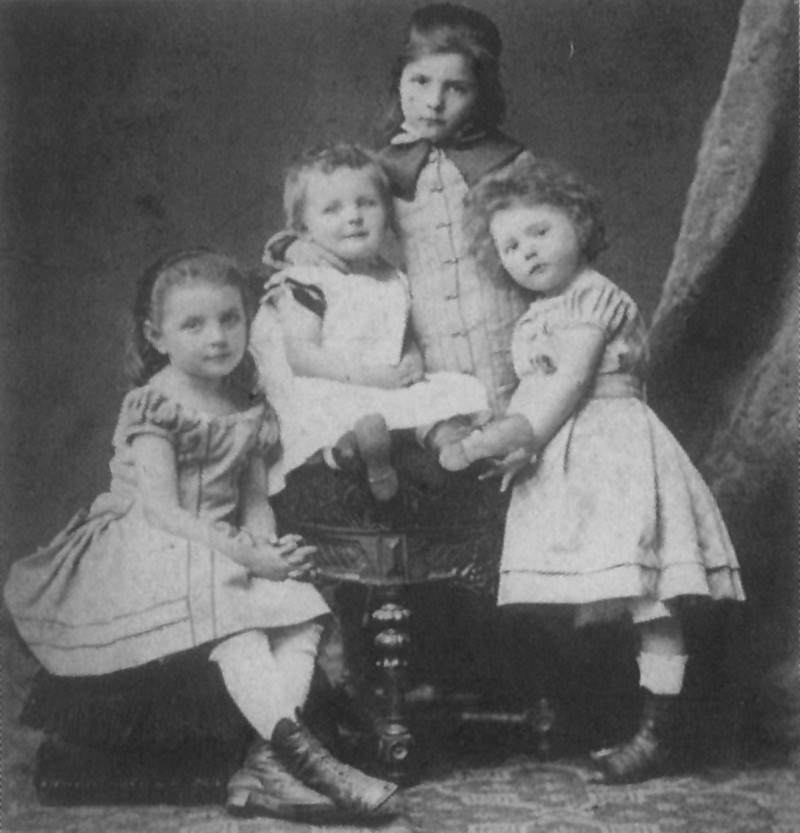

Siblings: Ernst, Wilhelm, Lotte, Rebecka, Anna

She earns a degree in chemistry but is also active as a social worker, sociologist, women’s rights advocate, and political activist. Many of her talents and interests seem to have been passed down to her from her ancestors: Her passion for natural sciences from her grandfather Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet, a famous mathematician; her social empathy from her father, who came from family of physicians; her championing of freedom and democracy from her grandmother Rebecka Lejeune Dirichlet, née Mendelssohn Bartholdy; and her readiness to test boundaries from her mother Flora, who was active in the feminist movement. Along with her great-aunt Fanny Hensel and Fanny’s own aunt Dorothea Schlegel, she is one of those female descendants of Moses Mendelssohn who chart their own course in defiance of the conventional roles society expects of them.

Her parental home in Danzig, with its luxuriant garden, is a place of “lively political debate.” Her mother and her brother Walter, a member of the Reichstag (German Parliament), have Leftist sympathies, while her conservative father, a Bismarck admirer and a veteran of three wars, prefers to remain apolitical. “These often very impassioned debates taught me at an early age how important, but also how difficult, it is to take political positions, and that taking decisions is a serious matter.” She takes courses at Frauenwohl, a feminist association co-sponsored by her mother, to prepare for her matriculation examination, which she passes in Zurich. Here she goes on to study at the ETH University of Applied Sciences and becomes acquainted with the artist Käthe Kollwitz and the writer Ricarda Huch.

By 1896, Marie Baum has earned a degree as a natural science teacher. While working on her doctoral dissertation, the 22-year-old works as a laboratory assistant in charge of supervising 60 students, mostly men. This raises eyebrows at the Swiss educational authorities, but the young woman stands her ground. After having earned her doctorate and chemist, she proves her mettle at the Berlin patent department of AGFA, the conglomerate managed by her relative Franz Oppenheim, but she soon recognizes that science in the service of economic rationalization is not her true calling. In 1902 she embarks on a five-year stint as a factory inspector in Karlsruhe on behalf of the Interior Ministry of the Grand Duchy of Baden. “I have observed numerous children far younger than the statutory minimum age of 10 – some may have been as young as four – crouched over their work with sallow faces and hunched backs... The youngsters’ workday lasted 10 hours not including breaks; for the adult men, there was no maximum workday... that of the women had only just been shortened at the time from 12 to 11 hours.” While attending courses as a guest student of the university in Heidelberg, she gets to know the sociologist Max Weber and his wife, the feminist activist Marianne Weber, who becomes a friend and fellow campaigner.

In 1907, Marie Baum becomes director of the Verein für Säuglingspflege (Association for Infant Care) in Düsseldorf, a post she will hold for the next twelve years. Here she also serves for many years in the Bund Deutscher Frauenvereine (Federation of Women’s Associations) and coordinates the city’s wartime relief activities as of 1914. In Hamburg, she runs the Sozialpädagogisches Institut together with the women’s rights advocate Gertrud Bäumer. Until 1921, she serves as a delegate of the German Democratic Party in the parliament of the young Weimar Republic. At the Interior Ministry of Baden, she heads the Social Services division and sits on the Governing Council; one of her projects is the establishment of a convalescent home for children. In 1931, she goes on a three-month lecture tour of the United States. Her professorship in social welfare issues at the University of Heidelberg is revoked by the Nazi authorities in 1933 due to her mixed-race status as a “second degree Mischling.”

In her autobiography Rückblick auf mein Leben (“Looking Back at My Life”), Marie Baum expresses her shame over initially having tried to contest her dismissal based on “the Mendelssohns’ commitment to the Christian faith.” She reluctantly admits that the “defamation that had been imposed on me personally” had caused her anguish for some time. But her ultimate decision in favor of the “other Germany” is unambiguous. Upon hearing that a doctor in Mannheim who had been spared due to his non-Jewish wife has voluntarily boarded a Jewish deportation train, she feels a pang of conscience: “I too, should have accompanied the deportees.” Her efforts to assist persecuted individuals do not go unnoticed and she is visited several times by the Gestapo. During one interrogation, an officer screams at her: “Why did I not simply emigrate myself, he demanded to know, given that I considered the government so distasteful? ‘Because I’m 67 years old and have always faithfully served my country,’ I replied. He departed, leaving a sulphurous smell in his wake.”

Once World War II has come to an end, Marie Baum resumes her lectures on social policy in Heidelberg, where she lives until her death at the age of 91. Along with Alexander Mitscherlich and Dolf Sternberger, she co-founds the action committee Freier Sozialismus. Politically, her sympathies lie with the Social Democratic Party (SPD), but she does not become a member. Having published her first monograph in 1906 (Drei Klassen von Lohnarbeiterinnen in Industrie und Handel der Stadt Karlsruhe (“Three Classes of Female Wage Laborers in the Industrial and Commercial Sectors of the City of Karlsruhe”), she goes on to publish books on family welfare services, edits the Diary of Anne Frank (1950), and writes several appraisals of the work of Ricarda Huch, her closest confidante over more than five decades. It is her friendship with this poet that awakens her own interest in historiography as well as a personal rapport to the Christian faith in accordance with St. Augustine’s precept of “love, and do what thou wilt.”