Leni Yahil

The ZionistFather: Ernst Westphal

Mother: Helene Westphal

Siblings: Hans-Carl, Dorothea Agnes Helene, Barbara Elisabeth Charlotte, Cecilie Clara Anna

Leni Yahil is born in 1912 in Düsseldorf as Helene Erna Wilhelmine Westphal and grows up in a family that feels indissolubly bound to German identity. The youngest of five siblings, she is very close to her Jewish maternal grandfather, the Berlin arts patron James Simon. Her first Hebrew-language book, a Bible with German translation, is a gift from Simon. Her father Ernst Westphal, who was baptized, is a judge, a patriot who served on the front lines of WWI and becomes a judge of the administrative court in Potsdam. This is where Leni attends a secondary school for girls that emphasizes modern languages and natural sciences. She studies history in Berlin and Munich and attends lectures by Rabbi Leo Baeck at Berlin’s Higher Institute for Jewish Studies. In 1928 she joins the Reichsverband der Kameraden, a patriotic youth group inspired by the Wandervogel movement seeking to get back to nature and to experience greater freedom from social strictures. Her guiding civic ideal consists of “a focus on the values of Judaism” coupled with “a commitment to German national identity.”

In 1932, Leni’s society of Kameraden (Comrades) re-invents itself as the Werkleute (Workmen), a “German-Jewish youth association” dedicated to: “... education tailored to shaping a Jewish person who, in his disposition and conduct, rebuts the distorted image of Jews that arose during the Galuth (exile).” Once the Nazis come to power, the first members of the association leave for Palestine to establish new kibbutzim and live there. Leni Yahil follows suit in October 1934. At first she works as an orange packer in the countryside, but then manages to continue her studies at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Two of her siblings emigrate to South Africa.

On March 8th, 1933, Leni’s father Ernst Westphal circulates an internal message in the court in which he protests against the draping of a swastika flag outside his courthouse. He is forced into retirement, also in view of his Jewish background. The children already in exile eventually manage to procure exit visas for their parents, but these arrive too late in Berlin, the war having already broken out. Over the next six years, Ernst and Helene are forced to move from one flat to the next and, after going undercover, from one hiding place to the other. Leni’s Aunt Elisabeth takes her own life before her threatened deportation can be carried out. Leni’s Aunt Marie, widow of the banker Franz von Mendelssohn, can be taken to safety abroad after a ransom is paid to the SS. Ernst Westphal survives the war but commits suicide in South Africa in 1949. Leni reflects on this tragedy five years before her death in Israel at the age of 95: “His whole world, the one he had understood and experienced, had come crashing down.”

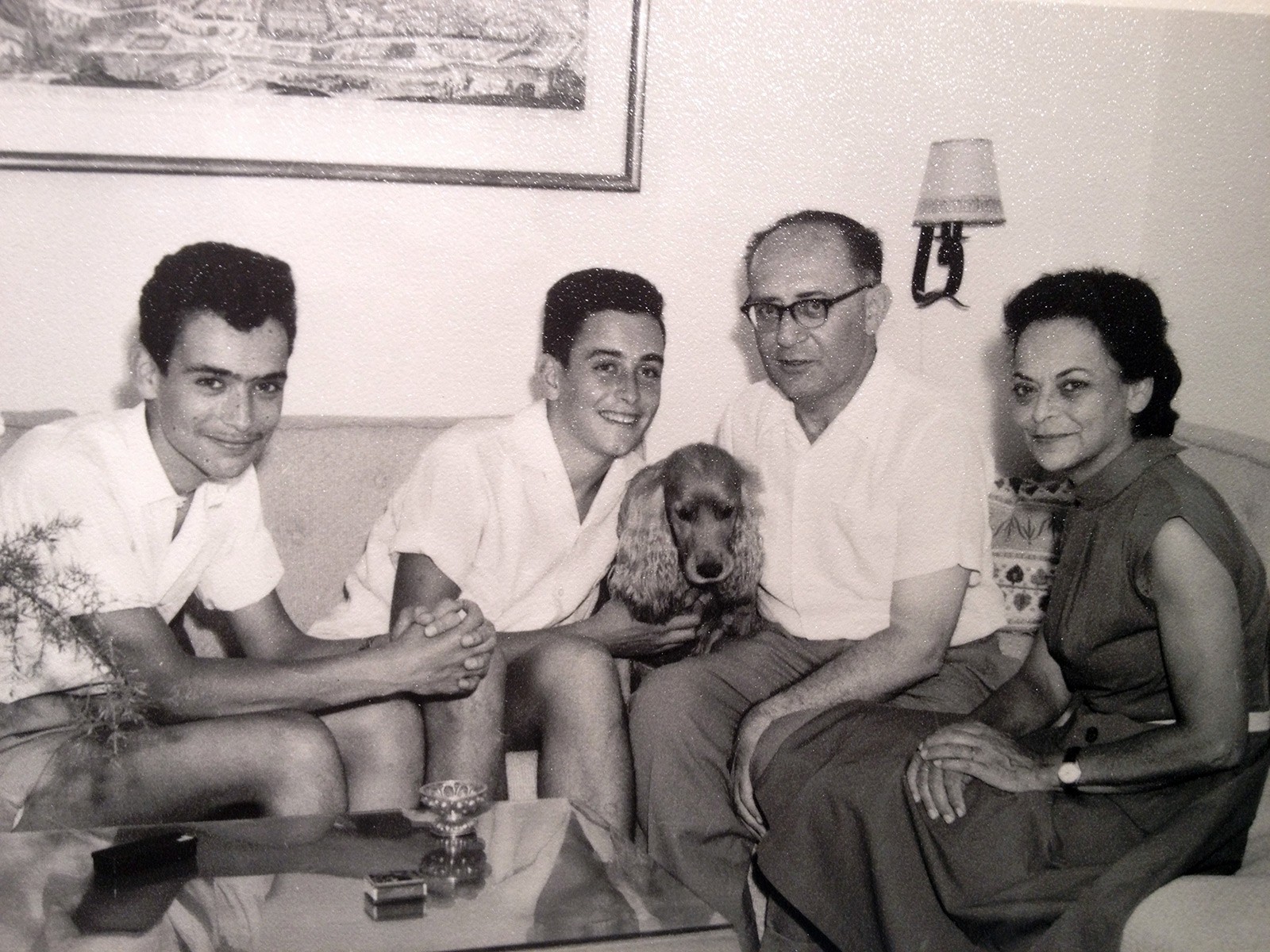

In 1942, Leni marries the political scientist Chaim Hoffmann, a newcomer to Palestine from Czechoslovakia who adopts the Hebrew name “Yahil.” Their sons Amos and Jonathan are born in 1943 and 1945, respectively.

Over the years, Leni Yahil repeatedly subordinates her work as a historian to the exigencies of her husband’s professional career: After serving as the Jewish Agency’s emissary at various European Camps for Displaced Persons, Chaim Yahil becomes the Consul of the young state of Israel’s in Munich. He negotiates with the West German government on the restitution of Jewish assets and is appointed Minister to the Scandinavian Countries in 1956. While living in Stockholm during her husband’s ambassadorship, Leni compiles material for “The Rescue of Danish Jewry: Test of a Democracy,” her doctoral dissertation. Later, when she is a professor in Haifa, her work on the staff of the Yad Vashem Memorial and as a visiting professor in the United States solidifies her reputation as one of the foremost authorities in the field of Holocaust research.

In 1961, Leni Yahil meets the philosopher Hannah Arendt and they become friends. In 1963, the two carry on a disputation by letter with respect to Arendt’s reports on the Eichmann trial. Leni Yahil objects to Hannah Arendt’s construct of the “banality of evil” as an explanatory concept: She refuses to accept Arendt’s contention that someone like the organizer of the Jewish genocide cannot rightly be accused of murder since he was merely the marionette of a totalitarian system and thus had been robbed of his ability to think independently. Leni argues instead that most people in the “Third Reich” most certainly did have moral benchmarks to go by, but that these were repressed wherever they would have had to take a stance regarding the plight of the Jews. In addition, she objects to Arendt’s blanket condemnation of the Judenräte (Jewish Councils) who were forced to collaborate in implementing the genocide, as well as to the philosopher’s attacks on the ideals of the State of Israel. The two women’s friendship does not survive this bitter dispute. Though Yahil writes a conciliatory letter in 1971, she receives no reply.

For Leni the historian, the rupture also inspires the way she decides to structure her magnum opus on the Shoah: Her emphasis on the Jewish perspective and more nuanced evaluation of the role of the various Jewish Councils and of the Jewish resistance movement can be understood as a reaction to the positions taken by Hannah Arendt: “More than anything else, it is important that the image [of the victims] made faceless and shapeless by the Nazis be restored.” Thus, her history of the Shoah relies to a greater extent on Jewish sources than did prior standard works on the subject, and she shows how the perpetrators, with their will to destroy, and the victims, with their will to survive, exerted a reciprocal influence on one another. Leni dedicates the scholarly tome to her late husband Chaim Yahil and to her son Jonathan, a casualty of the Six-Day War, “... both of whose greatest concern was the restoration of Israel.”