Francesco von Mendelssohn

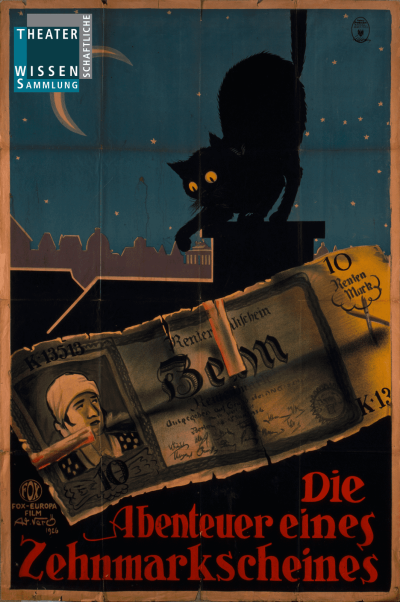

The EccentricFrancesco and his actress sister Eleonora, both Bohemians from the millionaires’ row of Grunewald, are friends of Berthold Viertel. Francesco’s one and only film role shows him at the age of 26, in the midst of the art scene at the apex of the Zeitgeist, surrounded by dizzying change all around. Given that the young man has no realistic appreciation for money whatsoever, his involvement with this now-lost silent film, a critically acclaimed satire against Capitalism, is merely an aesthetically pleasing entertainment.

The eccentric “Cesco,” who can sometimes be seen strolling along the Kurfürstendamm in his lemon-yellow dressing gown, ranks as one of the glamourous celebrities of the day. His father Robert dies in 1917; his mother Giulietta, a member of Italy’s Fascist party, later lives mostly in Florence, estranged from her children. The peaceful banker’s villa on Koenigsallee becomes a well-known location for the wild parties frequented by up-and-coming luminaries and friends such as Yvette Guilbert, Artur Schnabel, Vladimir Horowitz, Gustaf Gründgens, Wilhelm Furtwängler, Paul Wegener, Fritz Kortner, and Elisabeth Bergner. Francesco has none of his family’s business acumen, but feels all the more beholden to its cultural tradition. Using the precious “Piatti” cello by Stradivari he inherited from his father, he plays in concerts and is a member of the Klinger Quartet from 1926 until his involuntary departure in 1929. He publishes an illustrated book to commemorate the theater diva Eleonora Duse, a late friend of the family, and translates plays by Pirandello. His abortive career as a cellist motivates him to try his hand in the theater and he organizes a revival of the Threepenny Opera together with director Erich Engel. Starting in 1930, he mounts his own productions of contemporary plays in Berlin and Leipzig, but usually garners negative reviews.

As an openly gay man who has been categorized as a “quarter Jew” by the Nazis, Francesco leaves Germany a few days before Hitler’s accession to power. He goes on to stage the Threepenny Opera in New York (1933) and in Paris (in 1937, with Bertolt Brecht). In the United States, the non-acclimated, once pampered emigré comes into increasing conflict with the puritanical, middle-class ethos. A famous photo from 1935, full of hope and promise, shows Francesco and Eleonora with Kurt Weill, who was to compose the Biblical Broadway spectacle “The Eternal Road” for Max Reinhardt, along with Weill’s wife Lotte Lenya and the Zionist producer Meyer Weisgal, the five of them having just landed in New York Harbor. Francesco’s first home in Manhattan is a small townhouse on 83rd Avenue that soon becomes known as a party den. He is hired by Max Reinhardt as a director’s assistant for “The Eternal Road.”

But Francesco does not last long in this job requiring him to commit himself, nor can he hold down the job as a cellist he obtained in the orchestra of Arturo Toscanini through the good offices of Eleonora, who is the famous conductor’s lover. Hired by a provincial Texas orchestra during the 1940s, he departs after only two and a half seasons. While still in Europe, the siblings were able to sell off family artworks to obtain cash. In America, they are now dependent on dwindling grants from the Mendelsohn Family Foundation and on odd jobs. Yet they still do what they can to help other emigrés’ obtain US visas by providing affidavits of support as sponsors.

Francesco plans to write a chronicle of his family but manages to complete no more than a somewhat idiosyncratic layout for the work, whose chapters range from Moses Mendelssohn and “The Uninteresting Mendelssohns” to his own celebrity pals of the 20th century and period of exile (“and the others to come”) with its “Crazy Americans.” He plans to devote an entire chapter to the “divine” Eleanora Duse. After having remained stateless for many years, Francesco makes an unsuccessful bid for US citizenship. His run-ins with the system of law and order bring the rebel into hot water. He is repeatedly arrested for flagrant homosexual activity and drunkenness and committed to psychiatric wards, where is even subjected to electro-shock “therapy.” His breakdowns become more frequent and severe while his sister, her own strength failing, tries her best to care for him. While he is in the hospital following a stroke, she takes her own life.

Yet he is destined to survive Eleonora by 21 years, first as a patient in various clinics, where he is tortured with horrific treatments, then as a ward of his New York psychiatrist Fritz Wittels, and finally as a houseguest of Wittel’s widow. Students of the nearby Juilliard School are paid to occasionally accompany him in musical sessions at the apartment on New York’s Central Park. His violoncello from 1720, despite having been used for hair-raising sliding runs through Manhattan’s underbrush, is restored to its original sound and becomes the property of the Marlboro Foundation after Francesco’s passing. The foundation sells the instrument to the Mexican cellist Carlos Prieto, while donating the proceeds to a foundation that helps music students buy suitable instruments.